|

WEB-EXCLUSIVE

DESCENDANTS OF ATILLA, GENGHIS KHAN LIVE IN AMERICA By IREK BIKKININ For The New Mexican Article was published in The Santa Fe New Mexican, February 22, page B4. Have you ever heard of Tatars? Probably not. "I am a visiting journalist from Russia, but I am not an ethnic Russian. I am a Tatar." I repeat these words here in America many times. And almost every time my words elicit nothing but blank stares. When I ask Americans if they have heard of the famous tennis player Marat Safin, they usually answer by saying something like this: "Oh, yes. He is the Russian guy who won the U.S. Open in 2000." "No," I respond in frustration, "Marat is a Tatar, not a Russian."

Marat Safin, winner of the 2000 U.S. Open, is a Tatar also. Photo by the Associated Press. Very few people in the West know that Rudolf Nureyev, the greatest ballet dancer of all times, was an ethnic Tatar. He is considered to be a Russian genius, though his nickname was "Fiery Tatar." Like the best of us, he repeated at every opportune moment that he was not a Russian. He even explained publicly the difference between the Russians and the Tatars as follows (this is not a direct quote, but is based on one): "Tatars are more fiery and sensitive." Modern Tatars, a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority in Russia, are considered by some historians to be the direct descendants of those ancient warriors who ruled over most of the Asia and a part of Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries. But most scholars emphasize the complexity of modern Tatars' historical roots. Traditions of statehood among the Tatars and their ancestors, different Turkic peoples, go back to ancient times. They moved to Central Asia from the Middle East, from Palestine approximately 4,000 years ago. Ancient Turkic tribes built many states during their history, including the Hun Kingdom (376-454) and the Avarian Khaganate (562-803) in Central Europe. The first enormous Turkic state, the Great Turkic Khaganate, was established in 552 A.D. Its eastern extreme was Korea, and the western border was on Danube River, now Romania and Bulgaria. Less than 700 years later, in 1240-42, Tatars and Mongols together established the biggest state ever in the history of mankind, uniting most parts of Europe and Asia. This superstate later broke up into several smaller states, one of which, the Kazan Khanate, was subsequently subjugated by Russia in 1552. That year was the most tragic year in the whole Tatar history, because it marks the end of the Tatar statehood and the beginning of the centuries-long process of forced assimilation and russification of Tatars. Fast forward to modern times. The Bolsheviks, trying to preserve the cohesion of the multi-ethnic state, established a tiny autonomous republic for Tatars, called Tatarstan. Its territory now is even less than that of South Carolina. Only a quarter of all Tatars live within Tatarstan. Most are dispersed all over Russia and some live in such countries as Australia, Canada, Finland, Germany, Turkey and the United States. Two generations of Tatars now live in America. They represent the old and the new Tatar immigration. The first group's way to America was very long and tortuous. Most of its members started their journey as refugees from Russian Bolsheviks and settled in China, Korea and Japan. In 1949, they fled from the communists to Australia, Turkey and Japan. Many then moved to America in the 1950s. The old Tatar immigration is represented by such prominent people as Sagid Salah, nuclear engineer in Vienna, Va.; Onur Senarslan, a professor in Washington, D.C.; Uli Schamiloglu, associate professor of Central Asian studies at the University of Wisconsin. The new Tatar immigrants came to the United States mostly after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Roald Sagdeev, the former director of Russia's Space Research Institute and scientific adviser to former Soviet President Gorbachev, emigrated from the Soviet Union after marrying Susan Eisenhower, the granddaughter of the former U.S. president. He currently teaches at the University of Maryland. Another Tatar, Vil Mirzayanov, one of the most prominent experts in chemical-weapons production, was imprisoned in 1992 for revealing to the world that Russia had secretly developed a powerful binary nerve gas. He teaches at Rutgers University. These are just two of the many prominent and not-so-prominent Tatars living in the United States. In the world of sports, some Tatars play in the National Hockey League. Tatars have always been comfortable living in two cultures or two civilizations simultaneously. For this reason, Russian rulers frequently used Tatars as ambassadors, envoys, messengers and couriers. This particular quality of the Tatar people might come in handy now, when Russia and the United States are trying to establish a closer relationship. It is obvious that Russia will be a strategic partner and ally of America in the nearest future. Tatars could play an important role in this partnership for two reasons. The first has to do with oil. Sept. 11 exposed the fragility of American dependence on Middle Eastern oil. Sooner or later the United States will have to look for an alternative source of oil. Russia is one of the major producers and exporters of petroleum. Tatar businessmen are actively involved in the Russian oil production. In the 1970s Tatarstan was Russia's major oil-producing region. Later, when Siberia became the center of the Russian oil industry, many experienced Tatar oilmen moved to Siberia to develop new oil fields. Among managers and leaders of the Russian oil industry, Tatar representation is disproportionately high. The second reason for U.S.-Tatar partnership has to do with Islam. It is estimated that by the year 2050 about half of the Russian population might be Muslim. Islam in Russia is growing, not only due to the higher rate of birth among Russia's Muslims, but also because more and more Russians are adopting Islam as their religion. The leaders of Russian Muslims are mostly Tatars. In a few decades, Russia's Muslims will almost certainly have a much greater influence on Russia's foreign policy than they do now. Fortunately, Tatar Muslims tend to be very moderate, peace-loving and modern in their views, which bodes well for the future Russian-U.S. relations. Therefore, it is in the interests of the United States to have a strong and stable Tatar community in Russia, to train young Tatars in the American colleges, to give them a good idea of what a real democracy and pluralism are. Russia must be a friend to America, not an enemy. The ethnic Russians are good and generous people. But most of them are afraid to make independent decisions. They like to be in a group, not to be responsible for anything. They easily break rules, but they are accustomed to obeying their leaders. Very often in the past, those leaders led Russian people to big dangers and bad life conditions. Tatars are different, though most of them physically look like Russians. Tatars usually have their own opinions on every matter; they easily criticize their leaders. Tatars do not obey their leader if they think the leader is not right. Their willingness to remove their leaders is one of the main reasons why they lost their medieval states. But this behavior is good for democracy. Tatars are also very family-oriented people. It's common knowledge in Russia that Tatars are much more active than Russians in business, especially in trade. A Russian joke, as an example, that shows how Russians perceive Tatars' entrepreneurial qualities goes like this: "The Soviet government announces a new government program of pensions to the veterans of the Kulikov battle (between Tatars and Russians in 1380). A Russian old man goes to the commission that establishes eligibility for this pension and asks: 'But where do I get the confirming documents, the battle took place about seven centuries ago?' To which the commission replies: 'We don't know, don't know - but the Tatars keep coming and bringing them!'" Tatars want to be in the same cultural and informational sphere as the West. That¹s why they want to switch to a modified English alphabet, which Moscow tries to oppose. Tatars are trying go get closer to America from behind the "iron curtain." They are a modern nation with issues similar to those facing Americans. Tatars want to know about the world. They want to share with the world. Their Web sites usually have English-language pages. This allows American readers to visit these sites, like the Web site of my newspaper The Tatar Gazette: www.peoples.org.ru/tatar/eng_index.html.

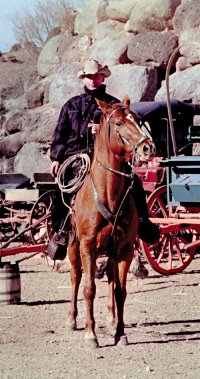

Like his ancestors who were horsemen, Khalil Vakhitov, a Tatar living in New Mexico, rides at a friend's ranch near Abiquiu. Photo by Irek Bikkinin/For The New Mexican Prominent Tatars Among prominent Tatars who contributed to Russian culture, science and economy are: Makhmud Gareev, general of the army, president of the Russian Military Academy; Albert Galeev, current director of Russia¹s Space Research Institute; Rashid Sunyaev, prominent astrophysicist; Rafael Yusupov, director of the Russian Institute of Information Systems and Automation; Renat Akchurin, a prominent surgeon who in 1996 performed a quintuple bypass surgery on Russian President Yeltsin; Rouslan Nigmatullin and Marat Izmailov, Russia's two best soccer players; Shamil Tarpishchev, the former Russian sports minister and member of the International Olympic Committee; Alisa Gallyamova and Gata Kamsky (1991 US Chess Champion), prominent chess players; Alsou and Zemfira, Russia's most popular singers; and Igor Fakhrutdinov, governor of the Sakhalin region of Russia. In New Mexico as a visiting journalist, I met these Tatars: Kamil Agi and professor Edl Schamiloglu, who live in Albuquerque. Both belong to the second generation of old Tatar emigration in America. Agi is a businessman and Schamiloglu works at Electrical and Computer Engineering Department of The University of New Mexico. I was amazed that despite being born here, both speak perfect Tatar.

Professor Ildar Gabitov from Los Alamos National Laboratory Khalil Vakhitov and professor Ildar Gabitov, who live in Los Alamos. They both emigrated from former Soviet Union. Khalil is an auto mechanic, and Ildar works in Los Alamos National Laboratory.

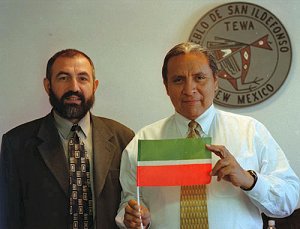

Irek Bikkinin, left, the author of this article, was chosen by the Tatar Internet community as Tatar of the Year 2001. John Gonzales, governor of San Ildefonso Pueblo, holds the Tatar banner. Photo by Jenna Naranjo/The New Mexican Editorial remark: Irek Bikkinin, a Tatar, is a newspaper editor in the Republic of Mordovia in Russia. He is at The New Mexican under a program for visiting journalists sponsored by the U.S. State Department.

© «THE TATAR GAZETTE» |