|

N 4-5, 10.07.2001

BROADCASTING IN TATAR: My work for the Tatar-Bashkir Service of Radio Liberty PART I Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Inc. (RFE/RL), so well-known in Eastern Europe and the former USSR, is the American-sponsored radio station broadcasting news and entertainment to the area beyond the former "iron curtain." Radio Free Europe was established in 1950 and broadcasts in the languages of Eastern Europe; Radio Liberty was launched in 1953 and broadcasts in the languages of the former USSR. Both radio stations were run by the CIA until 1971. In 1976 they were merged into a single entity - RFE/RL. Now it is financed by the US Congress and is supervised by the Board for International Broadcasting, whose members are appointed by the President. Today, RFE/RL is headquartered in Prague, but for most of its existence the main office was in Munich, Germany. In its heyday, RFE/RL employed thousands of people and also had offices in New York, Washington and Paris. Radio Liberty (RL) was organized into language services, with the largest, of course, being Russian. Of the non-Russian services, only the Tatar-Bashkir Service broadcast in a language of an ethnic group which did not have its own "union republic" within the USSR. All the other services — Uzbek, Tajik, Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian, etc. — broadcast for peoples that eventually gained political independence from Moscow in languages that are now the official tongues of newly-established nations.. My service with the Radio began in 1986, a few months after I came to the US following my escape from the USSR during a tourist trip to Syria and Jordan. I settled in New York, hoping eventually to become a US citizen. At that time, most members of the Tatar-Bashkir Service were stationed in Munich. The New York office of RL had only one Tatar employee - Mr. Enver Galim, the American correspondent of the Tatar-Bashkir Service. Mr. Galim was a frail man in his 70’s or 80’s. A former writer, who had been a prisoner of war during World War II and later settled in the US, Mr. Galim was a passionate anti-Communist and a devoted supporter of the Republican party. He lived alone in a small apartment in Queens, and had a dog named Muki. Muki was his closest friend and companion. My first meeting with Mr. Galim took place in the New York office of Radio Liberty. — "Hello, Sabirjan," he said to me in a raspy voice, stretching out his small bony hand. "Let me introduce you to my colleagues." Then he gave me a tour of the office, taking me from one room to the other. The office looked very ordinary: long corridors, covered with sound-absorbing rugs, several rooms and cubicles for employees, and a few recording studios. I was given my own cubicle. Inside, there was nothing but a table and an electric typewriter with Tatar Cyrillic letters. (Tatar can be written in either Latin or Cyrillic script. In the USSR, only Cyrillic was used and I was familiar only with that. Mr. Galim, however, as all of my colleagues in Munich, used typewriters with a Latin-based alphabet.) At the beginning, my Tatar, as well as my journalistic skills, were inadequate for the job I was given. I grew up speaking mostly Russian, and I had no political vocabulary in Tatar. But Mr. Galim was a patient teacher. He corrected my scripts every day and made me read them out loud before even considering them for broadcasting. Once Mr. Galim was finished with it, my very first script looked like a madman’s opus: almost every word was crossed out in red ink and replaced by another. Sometimes I even thought that Mr. Galim was intentionally mean to me. But with the passage of time his corrections became less and less frequent and eventually stopped altogether. The address of the New York office, 1775 Broadway, was also the title of one of the Russian Service’s most popular programs. The Russian Service in New York was represented by several correspondents, including such journalists as Yuri Handler, Peter Weil, Alexandr Genis, Boris Paramonov and Sergei Dovlatov (who eventually became popular in Russia as a writer). RFE/RL played an important role in dismantling the USSR. Most credit for the Radio’s important contribution to this goal is usually given to the Russian Service. Especial attention is given to the Russian Service’s promotion of various Soviet dissidents. In the early 1980’s, most Western experts on the USSR believed that it was the courageous struggle of these dissidents that was most likely to lead to any collapse of the USSR. As it turned out however, Western hopes were misdirected. While the collapse of the Soviet system was ultimately "caused" by the intrinsic contradictions within the Communist system itself, the catalyst of the collapse was the political awakening of the Soviet ethnic minorities. Radio Liberty’s steady broadcasts in the languages of the ethnic minorities over the Tatar, Estonian, Ukrainian, Latvian, Uzbek and other language Services thus played perhaps an even greater role in dismantling the Communist system than did any broadcasts by dissidents in Russian. Western hopes were wrongly placed in dissidents rather than ethnic minorities, which partly explains why the Russian Service (which was obsessed with dissidents) received so much additional attention and support. The non-Russian Services achieved this success even though most of them had only a few employees. In contrast, the Russian Service employed hundreds of people. Only the Russian Service could afford narrow specialization whereby one person wrote scripts, another person edited them, and yet another read them over the microphone. In the non-Russian Services, all these functions were usually performed by the same person. In New York, the non-Russian services had only one or two correspondents. Most people in the New York office were in their 40’s and older. There was not much interaction among members of different services. My shyness and my age (I was the youngest employee in New York) made it especially difficult for me to interact socially with other colleagues. In contrast, I felt completely at ease with the members of the Tatar-Bashkir Service whenever I visited Munich. Most of them became my friends.

Munich, Alpen. My first trip to Munich was in 1986. Mr. Garip Sultan, the Director of the Tatar-Bashkir Service, wanted me to come to Germany to get acquainted with my colleagues. At the airport, I was met by Mr. Ferit Agi, the Deputy Director of the Tatar-Bashkir Service. He drove me to a hotel near Radio Liberty. The Munich headquarters looked very different from the New York office. The office in New York was located at the busy intersection of Broadway and 57th Street and had no security. The Munich office, in contrast, looked like a big fortress surrounded by a stone wall painted white. It was located next to the Englishcher Garten (the English Garden), a large park in the center of Munich. To enter the office, one had to pass through elaborate security procedures. The Radio provided all the employees with free housing and furniture (hence, the furniture looked identical in every employee’s apartment). During my first visit to Munich, I had to stay in Monopteros, a small family-run hotel within walking distance of the Radio. Frau Kellenbach, the hostess, was accustomed to guests from the Radio, and seemed to know many of its employees. My German at that time was almost non-existent. She taught me some new German words and expressions. The next morning I went to the office of Radio Liberty at 67 Oettingenstrasse and met my Munich colleagues for the first time. I was already acquainted with Mr. Agi, whom I had met in Rome (while being processed as a refugee after I defected from the USSR) when he interviewed me for the job. Mr. Agi introduced me to the Director, Mr. Sultan. A tall, intelligent-looking man in his 60’s, Mr. Sultan resembled a Western politician more than a Tatar journalist. Everything in him seemed impeccable: manners, clothes, behavior. — "Glad to see you," Mr. Sultan welcomed me warmly in his flawless Tatar. He shook my hand and asked me about my impressions of the Munich office.

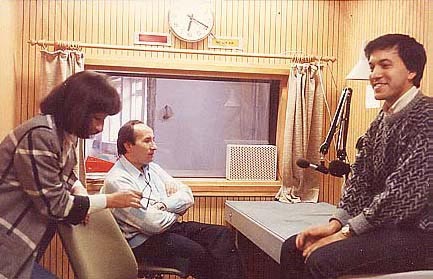

Farida Wahlroos, Hairettin Gyulechyuz and Sabirjan Badretdin in recording studio. After Mr. Sultan, I was introduced to my other colleagues: Hairettin Gyulechyuz, Ashraf Torpish, Farida Wahlroos, Gayaz Khakimoglu and Nuri Resuloglu. During my two-months stay in Munich I got to know them quite well. Like Mr. Galim, Garip Sultan had been taken prisoner during WW II and eventually decided to remain in the West. Soviet propaganda spread vicious lies about Garip Sultan’s past. As a result, to most Tatars in the USSR, he was known as "the person who betrayed Musa Jalil." Musa Jalil was a famous Tatar poet who had been executed by the Nazis for establishing a clandestine resistance organization among Tatar POWs in a German internment camp. The story about the "betrayal" was concocted by Soviet propagandists to discredit Mr. Sultan. As I got to know Mr. Sultan better, it became obvious to me that those accusations were not just false; they were completely ridiculous given Mr. Sultan’s personality and character. Hairettin, the head of a big family, was born in a Tatar village in Turkey. At the Radio he specialized in religious programming. Because of his knowledge of Islam and his ability to read the Koran in perfect Arabic, he was sometimes referred to as "our mullah" by our other colleagues. Although he had never lived in Idel-Ural (the ethnic Tatar homeland in Russia), his commitment to all Tatar things was deep and unwavering. Ashraf, a petite blond woman in her late 40’s was struggling with cancer. Despite her condition, she was always cheerful and friendly. In Munich she was frequently mistaken for a German woman, due to her North European appearance.

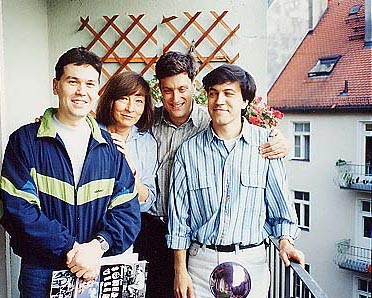

At the balcony of Farida's apartment - Nuri, Farida, a friend and Sabirjan. Farida, a Finnish citizen thanks to her marriage to a Finnish diplomat, spent her childhood in China and much of her later life in Turkey, where she and Ferit Agi were very active in local Tatar organizations. Farida spoke 6 languages, 3 of them (Turkish, Tatar and Finnish) with native fluency. An extraordinarily intelligent and charismatic woman, she felt under-appreciated at the Radio. This frequently led her into conflicts with other colleagues. Gayaz Khakimoglu, who lost a part of his leg when his aircraft was shot down in WW II, was a cheerful and talkative fellow prone to heavy drinking. He was born in Russia, became a POW during the war, and later settled in Turkey. He changed his last name from Khakimov to Khakimoglu out of gratitude to the Turkish state, which had granted him citizenship and helped him at a difficult time of his life. Nuri Resuloglu, a Crimean Tatar from Romania, was the youngest member of the Tatar-Bashkir Service. He was mainly responsible for the technical part of our work. The most impressive of them all was, of course, Mr. Sultan. His selfless dedication to the cause of Tatar freedom was awe-inspiring.

© «THE TATAR GAZETTE» |